It occurs to me that I need to be interesting

Travel notes from Kanto

After exploring Tohoku, I moved south into the Kanto Region, which, in addition to Tokyo, contains many other interesting places (including the fictional world of Pokémon).

The Kanto region, via Wiki image

I began in Nikko, the site of several temples and shrines. The town is surrounded by mountains, which some revere as deities.

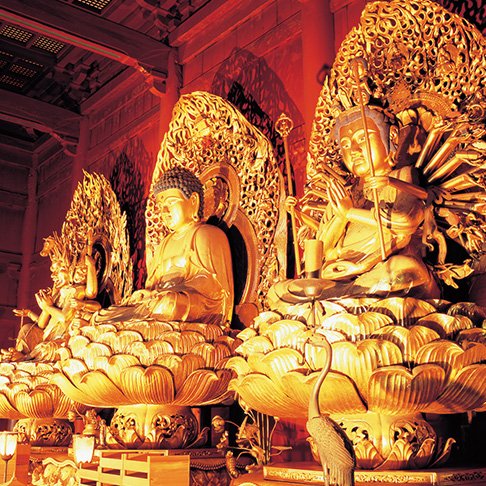

At the Rinnoji Temple, I saw three gold-lacquered Buddha statues that are described as manifestations of the three holy mountains around Nikko. In my notes, I commented that standing beneath the statues gave me a feeling of being overpowered: “Even the illumination from the lamps is from below, like holding a flashlight under your chin. Imagine this with flickering flame.”

The photos don’t do them justice. These statues don’t stand; they loom. You take them in by gazing upward from below, knowing that at any moment you could be crushed by the weight of their authority.

image: tobu.co.jp

Nearby is the Futarasan Shrine, dedicated to these three mountains: Mount Nantai, Mount Nyoho, and Mount Taro. I found the canopy of trees that close in around the site calming, and the wandering paths dotted with shrines and other places of worship felt almost like a bazaar.

Next was Taiyuin, the mausoleum for Iemitsu, the third shogun of the Tokugawa regime. The hushed space for prayer within the mausoleum was effective; equally memorable was a nearby temple dedicated to a close servant of Iemitsu. As I wrote in my notes, “Servants often committed suicide after lord died, but Kaji was ordered not to, instead tending to the grave and preparing his master meals as though he were still alive. Fascinating mix here of mercy with Sisyphus pushing the rock up the slope. Grief and memory and gratified and indentured servitude.”

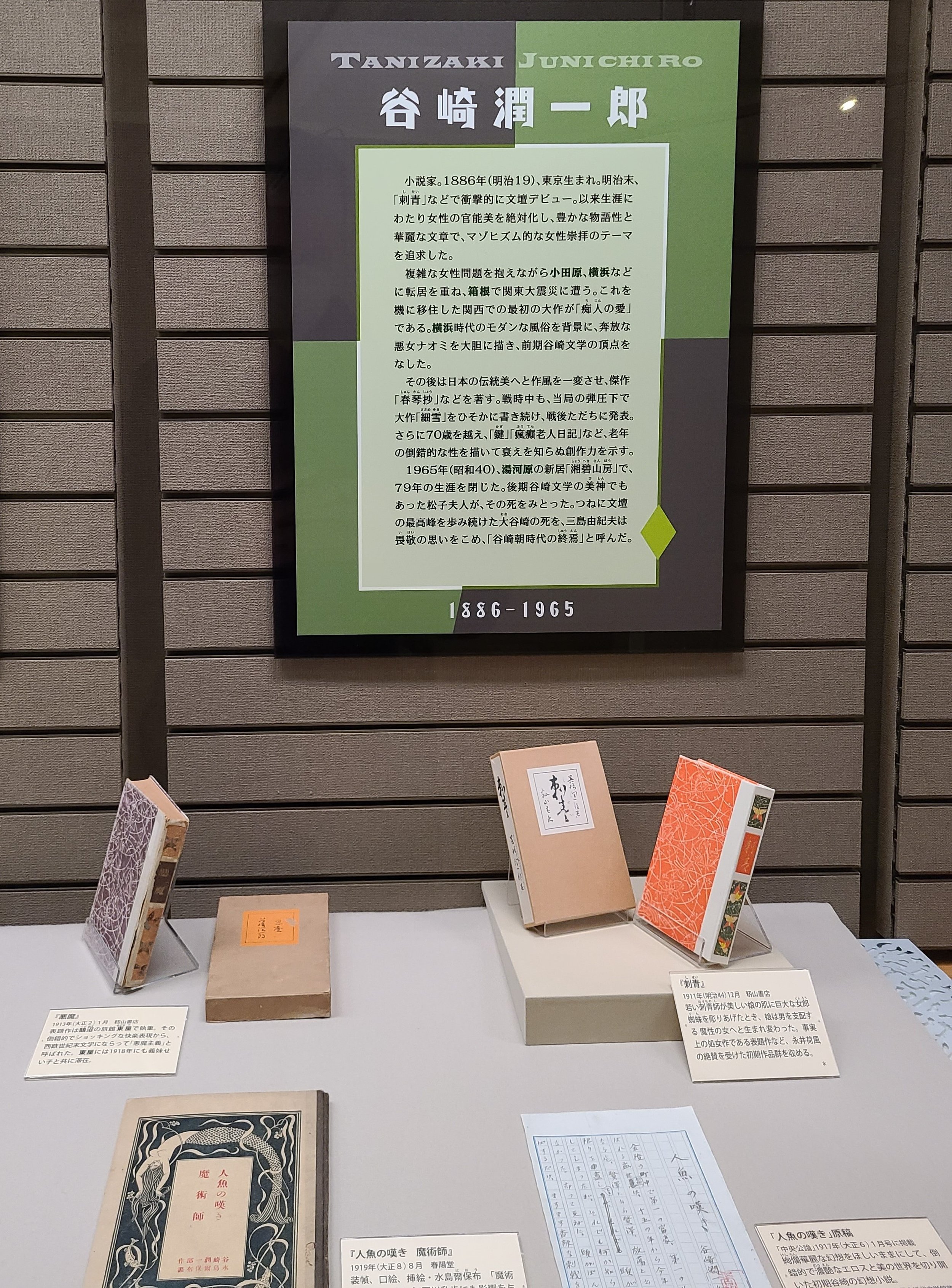

The main attraction of Nikko is Toshogu Shrine, dedicated to Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate (and Iemitsu’s grandfather). The site is full of treasures, from a “sacred stable” for horses, to a carved image of a sleeping cat (“nemui neko”) on one of the thresholds, to the mystical interior of the main hall. No photos allowed there, but in my notes, I wrote about a dim prayer room that contained painted phoenixes with glass eyes that you could just barely see in the darkness, as well as an “ineffable burnished disc,” all of which “made me appreciate what Junichiro Tanizaki said about the power of darkness.”

Standing a ways off from the shrine complex is the Tamozawa Imperial Villa, to whose elegant architectural beauty I had a full body reaction. I wrote, foolishly, “I want, I want...” Quite possibly the highlight of the trip.

The next city I visited was Kamakura, which lies a short distance south of Tokyo. This was my first real glimpse of spring: at Hasedera Temple, flowers were beginning to bloom. From the hillside above the temple, I wrote, looking down at the coastline: “People sailing, swimming, wading. I hear the sound of the train cars rattling, the crossing bell. Seagull caws. Hillside birds in the aural foreground. Is that whisper traffic or waves?”

Further on was the Great Buddha (“Daibutsu”) of Kamakura, where I jotted down, “Things that are big are just cool.”

I then made my way along the Daibutsu Hiking Trail, where I crossed paths with several townspeople out for a healthy walk. I admire the cultural value placed on walking and getting moderate intensity exercise here. Especially among people — the elderly, small children — I wouldn’t necessarily have expected to see on a rather steep hiking trail.

One of my favorite spots in Kamakura was Zeniarai Benzaiten Ugafuku Jinja Shrine, known — as a placard informed me — as “one of Kamakura’s five famous water.” Here, visitors can perform a ritual washing of their money in a holy spring, which is said to double the value of whatever bills and coins are rinsed in its waters. I watched an older man demonstrate the ritual for his grandchildren. The scene felt domestic and casually intimate, alongside its spiritual elements. I really liked it.

Next I visited Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine, which was absolutely buzzing. It felt like a carnival, with candied fruit stalls and music and many “games” to play amid the holy sites. A wedding ceremony was taking place on the mai-den (stage) as travelers watched.

An unexpected detail that moved me, as I recorded in my notes, was the “hundreds-of-years-old ginkgo tree that died in 2010 winter storm. Still standing, but no leaves to turn golden! And the wooden prayer tablets are still ginkgo leaf shaped. Some chief botanist must have died in shame.”

Just north of Kamakura is Yokohama, a port city that comes second only to Tokyo in population. I was struck by a photograph from 1910 showing the pier as it was then; I turned my gaze to the scene before me and took in the changes, while also trying to appreciate what was the same. A lot of history in one place.

A newer addition to the landscape is the Osanbashi Passenger Terminal, of which I wrote, “The brown-gray wood seems almost salty, the planar shapes suggestive of ships, the way the wind skims along its surfaces, the way it leaves one so exposed to the elements, and those elements themselves, the views and air and smell. Delightful! I want to sit here and unwrap a cupcake.”

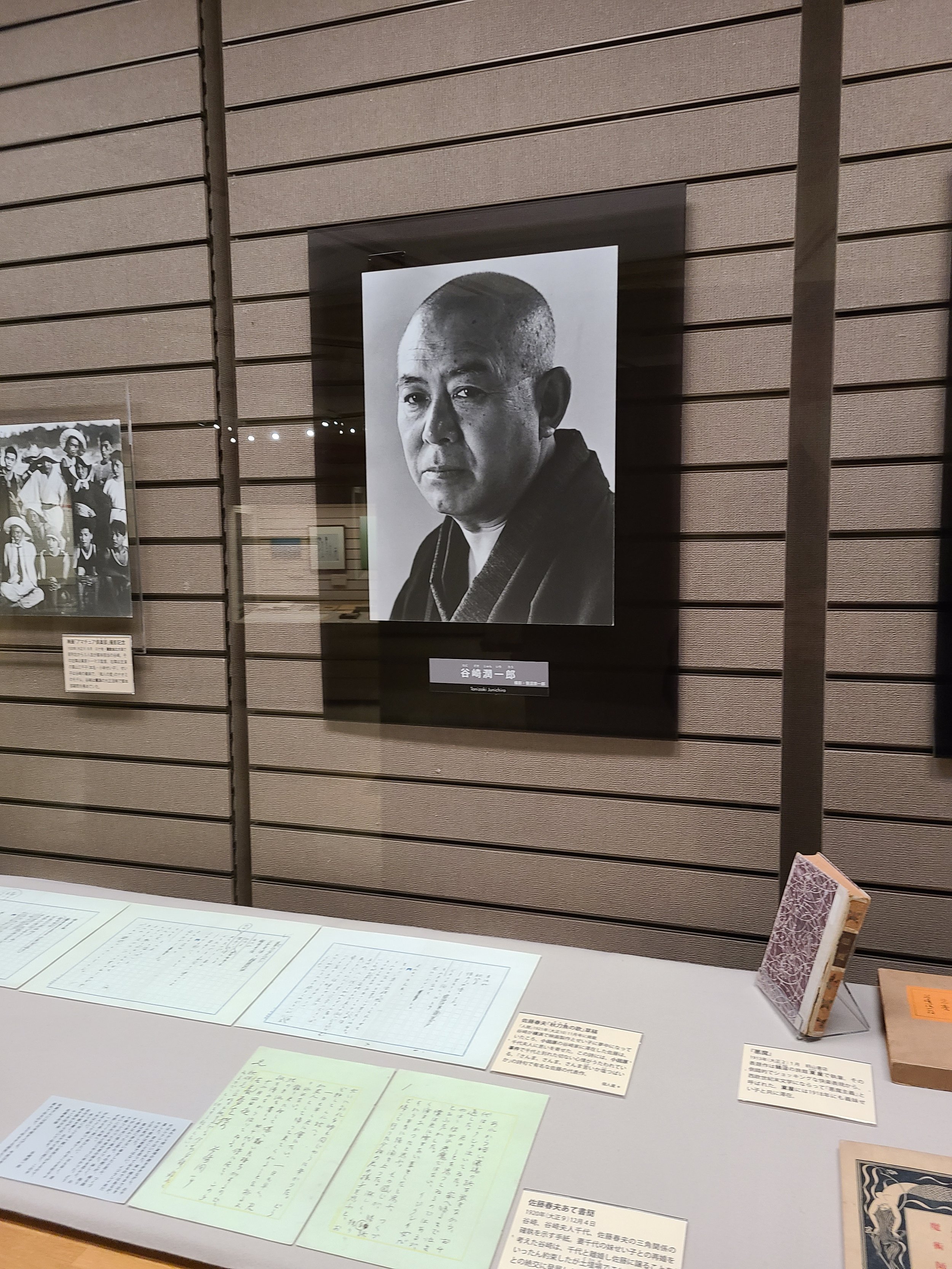

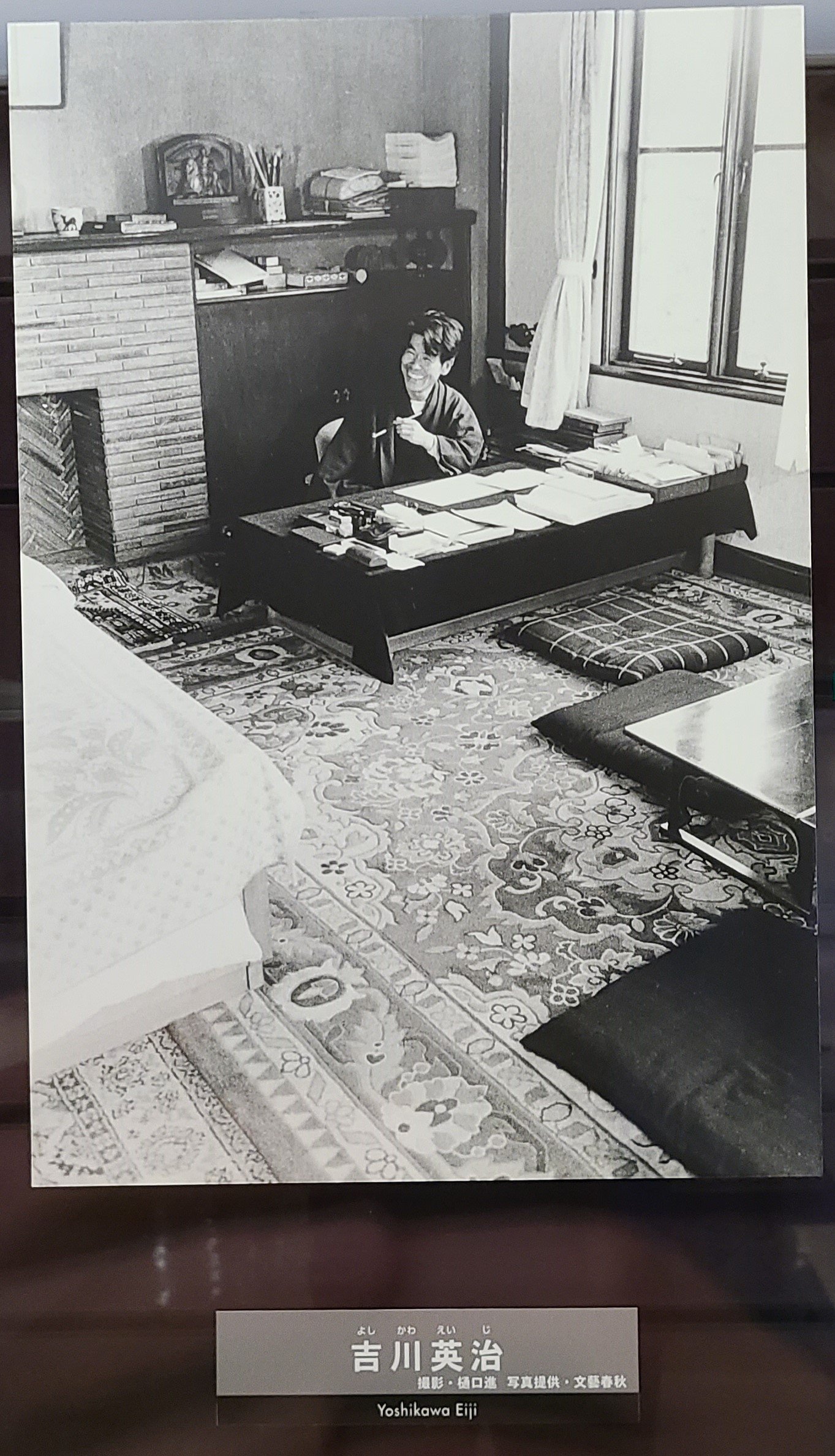

In a park nearby, I visited two literary museums: the Osaragi Jiro Museum and the Kanagawa Museum of Modern Literature. Given that my travels here are for a writing fellowship, I tried to absorb as much as I could from these displays of literary history and talent.

The Museum of Modern Literature’s exhibition was written only in Japanese, which led me to focus on the objects themselves: manuscripts and books, alongside photographs of famous writers, of which I noted, “These people all look smart.” There was something in the eyes that caught my attention, made me think about what sort of person comes to write fiction successfully, and what it might take to reach that state. “Am I inspired?” I wrote down. “It occurs to me that I need to be interesting.”

Elsewhere in Kanto, I made a jaunt north of Tokyo to Saitama. Here I stopped in at the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum; serendipitously, I had just read an article about an American bonsai apprentice who came here to study (and had rather a tough go of things).

The bonsai were exquisite, and I appreciated the opportunity to learn more about the craft itself. By miniaturizing trees, bonsai artists draw our attention to certain features with fresh, impressionable eyes. In my notes, I reflected that this process “made me think of Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go, and how compressing the lifespan brings out its constituent elements in seemingly greater intensity, urgency, and potency.”

The town itself has several bonsai nurseries, which are mandated to remain open to public access. On the day I was there, it began to rain, and — having forgotten my umbrella — I stumbled about the town more or less alone, soaking wet, watching water drip from the potted trees.

I eventually made my way to Omiya Park, where, as the downpour intensified, I took shelter under an awning at a children’s playground. There was a zoo nearby, although it appeared to be closed for the day. With little to do but huddle in a small dry space, I composed a haiku in English:

A spring rain

Soaks the standing trees

A monkey shrieks

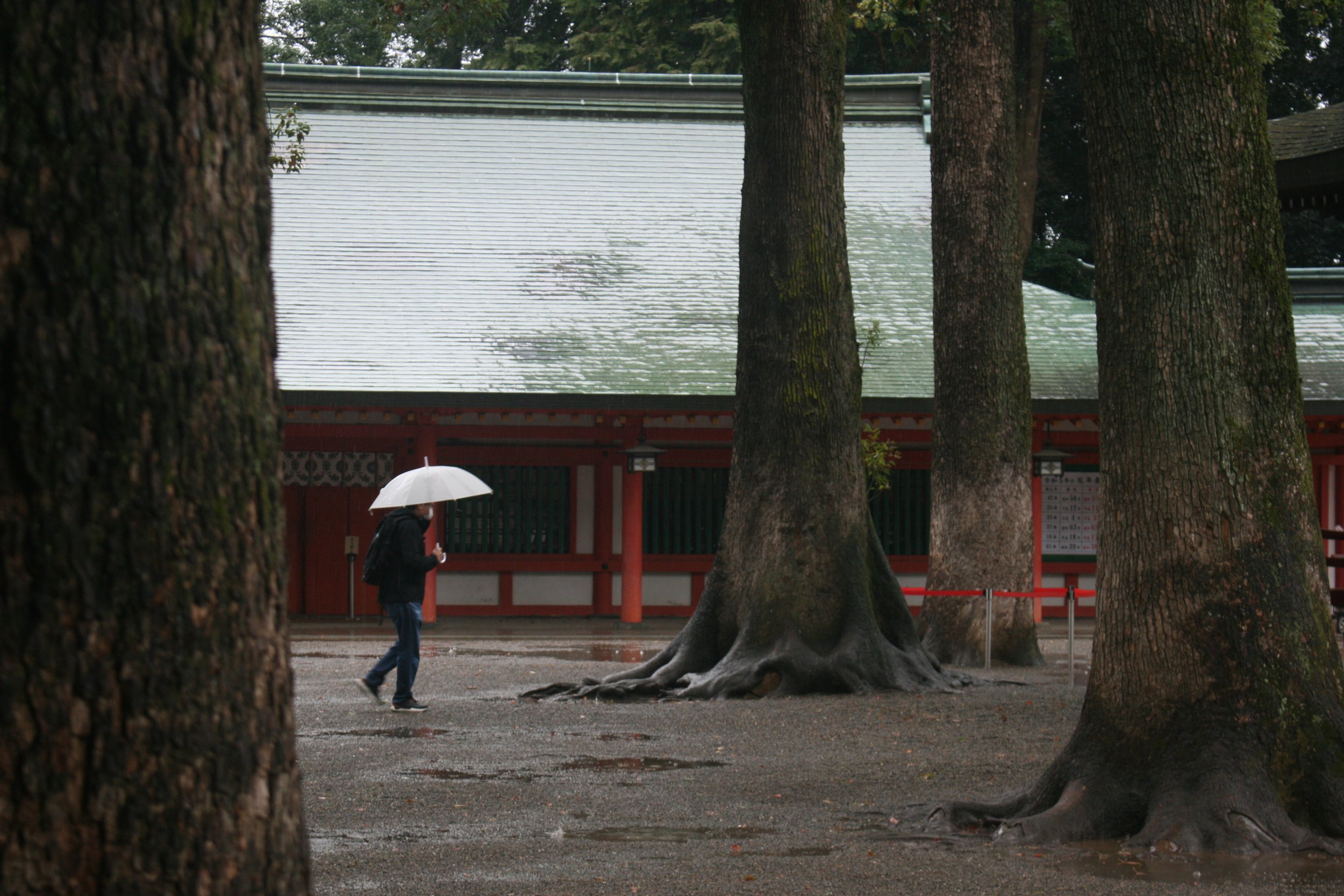

During a break in the rain, I darted to my final stop, Hikawa Jinja. This shrine has one of the longest paths of approach I’ve seen in Japan — taking up so much space that it forms its own city park.

Within the shrine, it seemed that the rain had kept away all but the most dedicated of worshippers. These included several families with small children, who were dressed adorably in rain coats and boots and sheltered by umbrellas held out by their guardians. I was glad to see it.

That was what I saw in greater Kanto; although, of course, Kanto also contains Tokyo, where I stayed for about a week and half and saw many other things.